It’s nearing the end of the semester. Teachers are writing final exams; students are presenting culminating projects. I’m visiting classrooms to see some of the exemplary work my colleagues and their students have been doing.

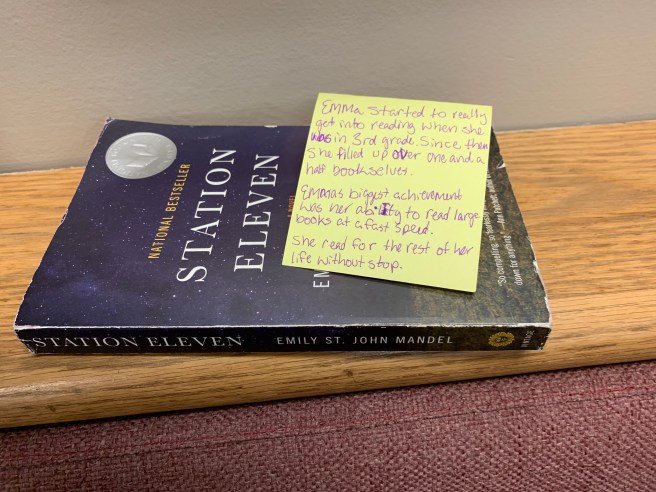

Earlier this week, my colleague Sarah Gessel and her students mounted an exhibition in the Media Center called the “Museum of Civilization.” It was a curation assignment, inspired by Station Eleven, a post-apocalyptic novel by Emily St. John Mandel that has become a staple of the English curriculum following an all-community read that our English teachers had a hand in designing.

A character in that novel establishes a “museum of civilization,” an exhibit at the deserted airport, of the world as it used to be. Mrs. Gessel wanted her students to understand how objects become symbols of individuals as well as of the collective. She wanted her students to understand that their individual dreams and ambitions, their likes and loves, their pastimes and pleasures, their actions and accomplishments encapsulate them as individuals and, collectively, characterize their generation. She wanted them to think critically about the objects in their lives that capture the essence of each of them. Here was Mrs. Gessel’s assignment:

Background: In Station Eleven, we learn that Clark is the keeper of the Museum of Civilization at the airport. There, he preserves items of the past that represent mankind before the flu.

Question: What three things would you personally put in a Museum of Civilization a hundred years from now that would represent you as a whole? You may not use a phone.

Assignment:

- Choose three items that represent you as a person.

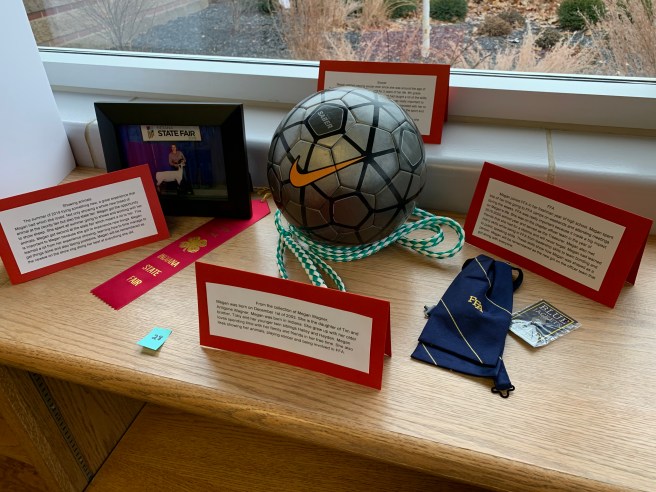

- Create a display “From the collection of ___________ (you)”. Your collection should contain a brief description of who you are (written in 3rd person!), including birth year.

- For your display, you must have the actual item. If that is not possible, a picture will have to do.

- For each item, you will create an informational label (like you see in a museum under an artifact). It should contain:

- The time period it is from

- Its use or symbolism

- Why the object was important to him or her

- What it tells the future about the person

- Here is a very basic, rough idea of what I am looking for…except yours should be real…not on a document.

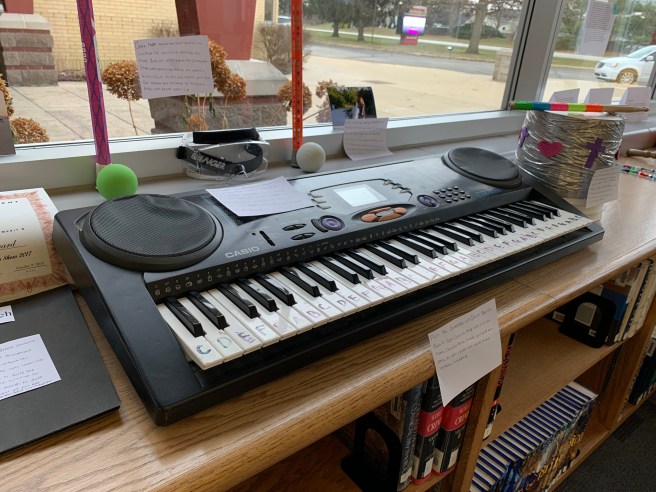

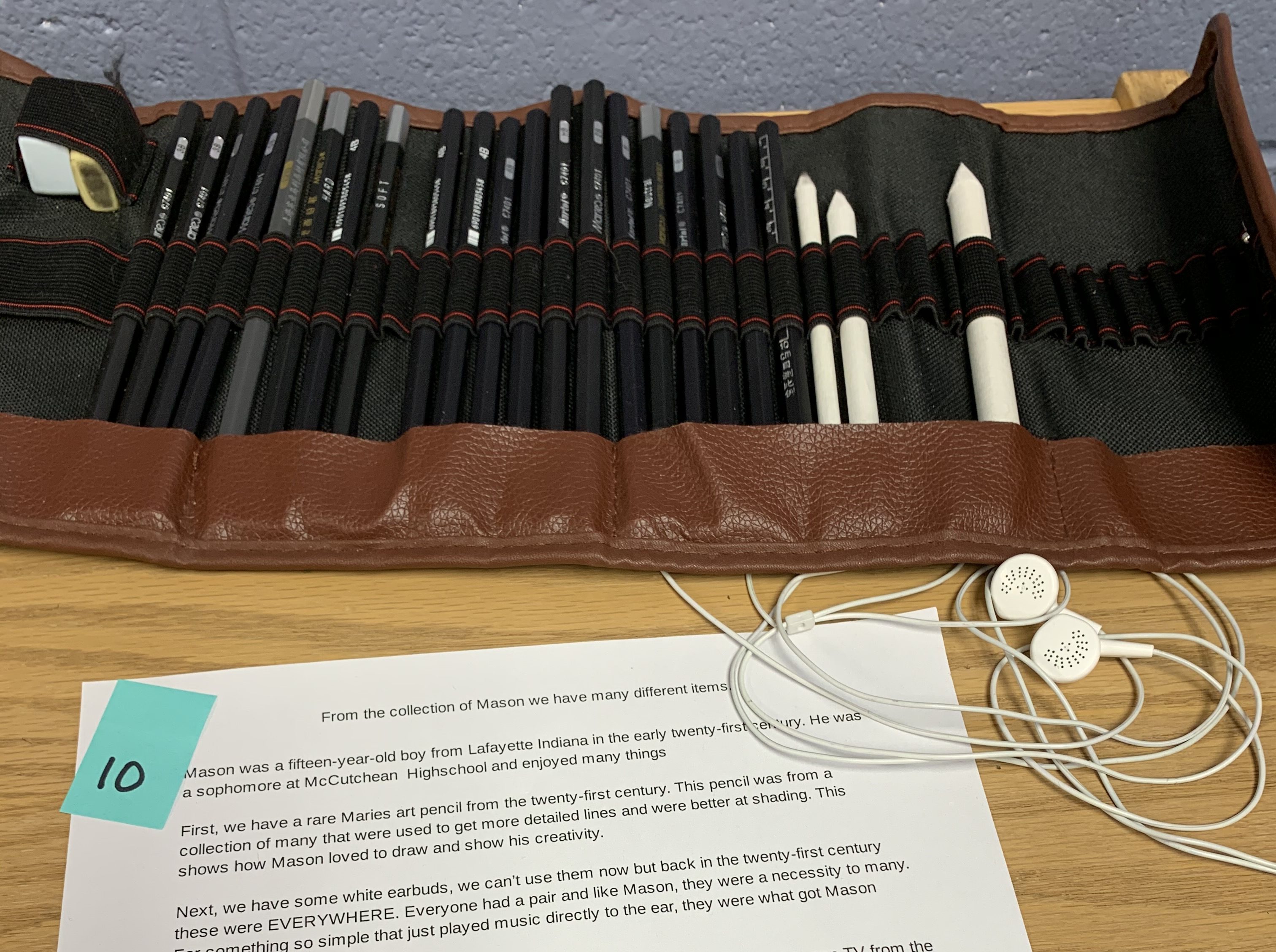

Here are some of the items students brought to school:

Some of their artifacts were poignant–a necklace made with a dear friend, now deceased; a stack of recipes from a grandmother; an old movie camera that launched what might well become a career:

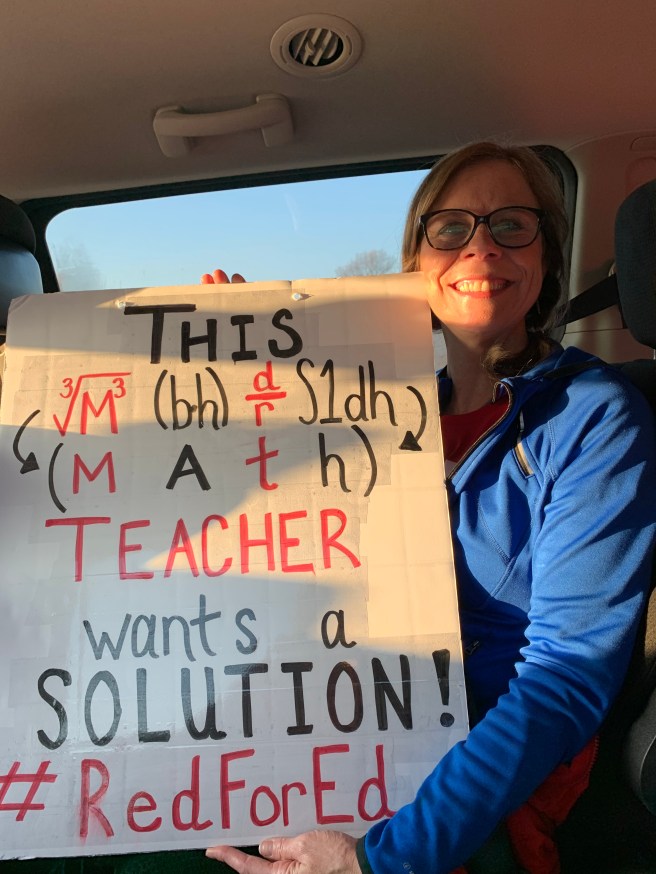

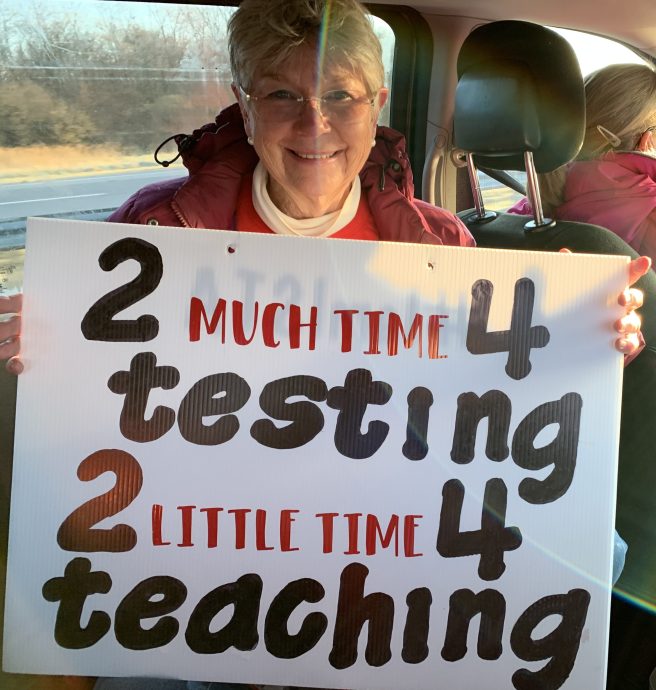

Yes, there were earbuds and screens, but not many. In fact, what I noticed in addition to the wide variety of artifacts was the overwhelming lack of electronics. Admittedly, Ms. Gessel forbade phones, but earbuds and other electronic paraphernalia did not dominate the displays. Instead, there were the indicators of family, friendship and faith. Of interest in the arts, organized sports, and individual artistic pursuits. In children, in 4-H, in books, in cooking. Ms. Gessel’s students, like most teenagers if critics would just look beneath the surface, are not the zombie-like, plugged-in and tuned-out youth so often caricatured. These are kids I want to know better, unique and interesting individuals who are going to be in charge of a world I want to live in.

Yes, there were earbuds and screens, but not many. In fact, what I noticed in addition to the wide variety of artifacts was the overwhelming lack of electronics. Admittedly, Ms. Gessel forbade phones, but earbuds and other electronic paraphernalia did not dominate the displays. Instead, there were the indicators of family, friendship and faith. Of interest in the arts, organized sports, and individual artistic pursuits. In children, in 4-H, in books, in cooking. Ms. Gessel’s students, like most teenagers if critics would just look beneath the surface, are not the zombie-like, plugged-in and tuned-out youth so often caricatured. These are kids I want to know better, unique and interesting individuals who are going to be in charge of a world I want to live in.

And here’s what happened afterward, after the spectators left, after the voting by gallery-goers was over, after the grades were assigned: The students looked at each other’s displays and something spontaneous occurred. Here’s what Ms. Gessel wrote to me:

My heart is full as I am sitting here thinking of the time we just spent last hour enjoying each other’s company as a class. All of their “stuff” is great, but what made so many of those items in there come to life were the kids. Watching them ask each other to play their instrument or sing or dance or compliment each other’s artwork or just comment on how nice it was just to chill with each other and listen…WOW. No museum can hold that amount of wonder or life. This is why I teach and am still teaching!

If you would like to know more about curation as an instructional tool, click here to read this article by Jennifer Gonzalez in Cult of Pedagogy.