Thys Boke is Myne Prince Henry: An inscription in a copy of Cicero, belonging to Henry VIII when he was a boy.*

What is it that makes us write our names in our books, amass collections of books, enthusiastically lend our books to friends (but keep a record so we can call them back)? When we do cull our collections and take stacks to used book dealers, why do we cross out our names or obliterate them with labels? If someone has inscribed a book for us—a gift—we hesitate to let it go, and if we have books passed down from our parents, our grandparents, their parents before them, well, these simply cannot be discarded.

Maybe I shouldn’t be using first person plural here. Maybe the problem is unique to me. But I don’t think so. I’ve seen too many crossed out names in books I’ve picked up in second hand stores.

Whatever else Henry VIII the adult was, he read widely as a child and even became a writer himself. I like to think that the impulse to write his name in his Latin book—to assert his ownership—was not just proprietary in the way he acquired weapons and wives, but that it sprang from the same impulse I respond to when I write my name in a book. When I say I own a book, it is not just the physical entity that I mean belongs to me. I am saying that the contents have become a part of me, have shaped my identity, and have influenced my thought. When someone I don’t know well looks at my personal library—whether at school or at home—I feel just a little bit invaded, like that person has a window into my mind, has gotten a glimpse of my soul.

Understanding this explains why, at a used book sale, I buy copies of books I already own—it’s as if I’m retrieving a lost part of myself. Thys boke is myne! Not the library’s, not Earl Avenue Books’, not Buy the Book’s. Myne!

For some years now, I’ve been collecting the books I read as a preschooler or during early elementary school years, repossessing myself, so to speak. I know these books not by title, but by their images. I’ve instantly recognized Me, Too (a fluffy yellow duck) and The Little Small Red Hen, both found resting unceremoniously in antique dealers’ cubbies. I have no trouble recognizing the Dick and Jane readers, primers peopled by those ever-ebullient, always co-operative, never unpleasant—but sadly, monosyllabic—children, Dick and Jane, and their little sister, Sally, whom I loved best because she had my name. And their pets: Spot and Puff.

On summer afternoons in upper elementary school, my best friend Anne and I were allowed to go downtown to the public library where, once we had exhausted the children’s collection, which was located in the basement, we moved to the junior high shelves, also in the basement. There, I discovered books that came in series: Little House on the Prairie, Anne of Green Gables, and the Betsy-Tacy books. Betsy Ray, growing up in a small town in Minnesota around the turn of the century, wanted to be a writer. So did I. I stuck with Betsy well into junior high. At one point during those years, two friends and I playacted the three best friends of the series, and I wrote to the author, Maud Hart Lovelace, to tell her of this marvelous fact: We fit her characters to a tee. She graciously replied, in her own hand, on a card that featured an illustration of Betsy, taken from one of the books. I still have that card, and as an adult, from used book dealers online, I bought the Betsy books I’d lost over the years. Pristine copies are collector’s items now, but I kind of like my worn library copies because the public library is where I first found Betsy.

Later, my friend Anne and I wheedled our way into the adult stacks, located upstairs. Attitudes about reading were different in the day. Librarians, I am sure, had a proprietary interest in the books themselves, and they seemed to disapprove of children getting “above” themselves, reading stories that were too old for them or books with words they surely wouldn’t know. I can remember having to tell a librarian once what a book was about in order to satisfy her need to be certain of my reading ability. Once we got upstairs and into the dark, towering stacks, Anne wanted to start with the A’s and read every book all the way to Z, but we got waylaid and then stuck in the H’s, captured by another series, this one by Grace Livingston Hill. But I went on to discover Carl Sandburg and McKinley Cantor and Sinclair Lewis, and I read many, many British classics that I took from those stacks.

In 8th grade, I traveled by train from my home in Illinois to my cousins’ home in Seattle. I brought a big book with me: Gone with the Wind. It was the first really thick book I’d read, and when I closed the cover on the last page, I remember feeling that I’d crossed some kind of threshold. I read two more fat books that summer: The Silver Chalice (I loved to swirl the name “Joseph of Arimathea” around in my mouth) and Not as a Stranger (considered risqué—even more evidence that I’d crossed some threshold). The poetry of Emily Dickinson—and Dorothy Parker’s acerbic verse—I remember from summer reading. Jane Eyre was a summer book sometime in high school, and so was Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (a recent choice of the book club I belong to!). The summer after my junior year, I gave my heart to Henry David Thoreau, whose Walden I still read and sometimes have been lucky enough to teach, and senior summer it was Huxley and Orwell who captured my imagination with Brave New World and 1984.

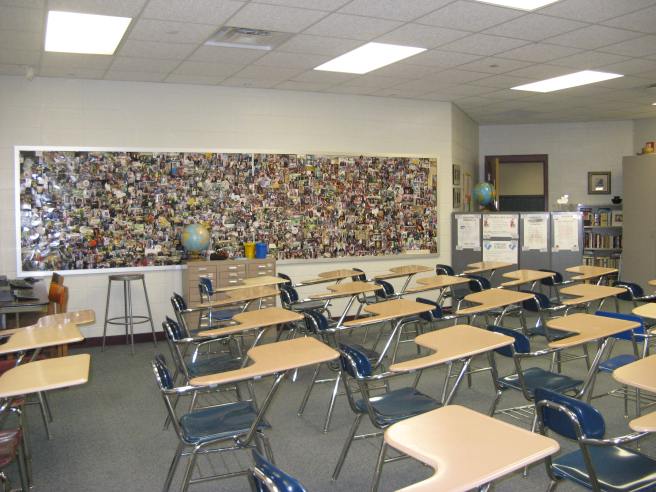

What does all this reminiscing about summer reading have to do with my American classroom? My teachers—and my parents, of course—encouraged me to read, both by example and by mandate. My first grade teacher taught me to read, and all of my teachers helped me to love books. Many of those teachers presented me with a summer reading list, knowing full well that it is in the long, languid days of summer that children and teenagers have the time and disposition to sink into books, abandon obligation, and let the characters and ideas therein become a part of themselves. When I left my classroom almost a month ago, I gave away my paperback books, the ones that had been housed in my classroom on a revolving display case, a hand-me-down from the school library. All year I’d been recommending the books on that rack; in the end, I offered them free to my students. They snapped them up. One boy needed a shopping bag.

I hope this is a summer of books for them. I hope they will love them, write their names in them, and make the contents their own. And I hope they will remember me, the giver. I did not erase or sully my name. I left it on the first page: Sarah Powley. Thys boke was myne.

And now, I am settling down with my own reading list, a mix of history and science and literature and books on instructional coaching. I’ll be back in the fall, rejuvenated, reeducated, and ready to take on my new responsibilities and resume this blog. Happy summer everyone! Happy reading!

*The Folger Shakespeare Library’s exhibit of people and their books, displayed during the winter of 2002-2003, took its name from Henry’s assertion of ownership.

In an American high school like mine, which is not so different from most, students come in all shapes and sizes with backgrounds so varied you are surprised they were raised in the same country, let alone the same community. They range widely in their abilities, their interests, their experiences, and their aspirations. Some have parental support so intense we call their mothers and fathers “helicopter parents”; others have no support at all. Some are from robust, supportive, intact families; others have survived dysfunction that boggles the mind—alcoholism, drug abuse, child abuse, divorce, and abandonment. Some are rich; others, dirt poor. They may speak perfect English, bad English, or no English at all. They may have traveled the world or seen only the corners of Tippecanoe County. They are the sons and daughters of bankers, business owners, teachers, farmers, industrial workers, lawyers, tradesmen and women, city engineers and school janitors. They live in trailers, apartments, bungalows, farm houses, and mansions on the prairie. Some even live in cars.

In an American high school like mine, which is not so different from most, students come in all shapes and sizes with backgrounds so varied you are surprised they were raised in the same country, let alone the same community. They range widely in their abilities, their interests, their experiences, and their aspirations. Some have parental support so intense we call their mothers and fathers “helicopter parents”; others have no support at all. Some are from robust, supportive, intact families; others have survived dysfunction that boggles the mind—alcoholism, drug abuse, child abuse, divorce, and abandonment. Some are rich; others, dirt poor. They may speak perfect English, bad English, or no English at all. They may have traveled the world or seen only the corners of Tippecanoe County. They are the sons and daughters of bankers, business owners, teachers, farmers, industrial workers, lawyers, tradesmen and women, city engineers and school janitors. They live in trailers, apartments, bungalows, farm houses, and mansions on the prairie. Some even live in cars.