This post is written by my colleague Laura Whitcombe. Laura has been a member of the English Department at McCutcheon High School since 1994. Her specialty is speech, and in addition to sponsoring the award-winning Speech Team, she teaches the required sophomore speech class, the Ivy Tech Dual Credit course for juniors and seniors, and the Vincennes Early College Advanced Speech for sophomores. Her students’ answers to a question she asked them this week should give us hope, reassurance, and confidence that they’re going to come out all right at the other end of this remote learning experience.

This post is written by my colleague Laura Whitcombe. Laura has been a member of the English Department at McCutcheon High School since 1994. Her specialty is speech, and in addition to sponsoring the award-winning Speech Team, she teaches the required sophomore speech class, the Ivy Tech Dual Credit course for juniors and seniors, and the Vincennes Early College Advanced Speech for sophomores. Her students’ answers to a question she asked them this week should give us hope, reassurance, and confidence that they’re going to come out all right at the other end of this remote learning experience.

What is going on inside their heads? The minds of teenagers remain a mystery, but even more so when we cannot be with them in person daily.

I read the posts written by education journalists and those who want to hand out advice. Just give feedback. Drop grades completely. The kids are traumatized. They are not the same kids as before we sheltered in place. But I don’t know… We aren’t in the Upside Down world of Stranger Things. We are just at home on our laptops.

On Mondays, my speech classes have virtual class meetings. None of us has ever done this before, so it is an evolution. At first, there were faces. Now there are avatars. I have asked a few what they are. But some I just leave alone. There are die-hard kids who always attend. There are hit-and-miss kids who sometimes show up. And there are kids whom I said goodbye to in my classroom and who never showed up online.

Most of my students are with me. More than half. Is that good? My academic classes have about 90% participation in meetings and assignments. My regular mixed-ability classes have between 60 and 70% participation. Some come for the meetings but don’t do the work. Some do the work but randomly attend the virtual sessions. I think that means that they feel good about the resources I shared. My videos, slideshows, document templates, examples, and calendars are providing students with what they need to do the projects.

But I don’t know for sure.

I have been wondering what inspired my students to keep working, so Monday I started the class by asking a question.

“What is keeping you going? What is motivating you to keep going to school?”

It was nice to call on each student individually by name. It was just like an attendance question in the classroom. It was nice to give attention to each student. In my classroom this is my habit and consistency is comforting.

I was surprised by the normality of their answers. Grades. Grades still matter. From academic seniors to special education sophomores, most agreed.

- They still want to try to do what they can do.

- They want to do their best.

- They are still thinking of the future.

- Some mentioned college.

- They see a need to learn and have these skills for college.

- They still need to earn their scholarships.

- They have goals and are worried about the same consequences as before the shelter-in-place.

- They said that they have self-discipline, and this is what they do: they get organized, build a schedule, and get things done.

- Some said that they finally developed or had to develop this discipline.

- They were proud that they have been able to make this remote learning work even if they did not like it.

I admire these students who stay motivated. I admire that they are still with us. Thinking back on my own teenage years, I feel like I would have flaked out and dropped out. My mom was a nurse and I would have been unsupervised and left to my own devices. Maybe. Maybe if my peers were like the students in my classes and kept focused, then I would not have wanted to be left out or left behind.

Other students added these comments:

- “What else am I going to do?”

- “This is easy on my own schedule.”

- “I am more relaxed because I can go at my own pace.”

- “There is lots of time for me to do my hobbies.” They listed painting, embroidery, hoops in the barn, raising animals, working out, and of course, video games and sleep.

- They showed me new turkeys, chickens, cats, dogs, and a couple of little brothers. They said that having the comforts of home was comfortable and comforting.

- Those with parents also working from home described an easy routine where everyone in the house goes to their own spots in the house to work online, then come together in the evening.

I am impressed by their natural ability to adapt. They have been in school for 10-11-12 years. They know what to do. Teachers have led them through their coursework before and are leading them from afar now. They are not suddenly alien-beings because they are not in seats in our rooms. We, students and teachers, have the same values we did before. We value sticking with challenges and overcoming obstacles. We always have and students are with us.

Of course, I worry about the students who disappeared, but right now I am here for those who want to learn. I will be there for the others when they come back when we are together again, however that happens.

I am so happy for my students. They seem fine. Fine. That is good. And being good might be good enough. For now.

Laura is a graduate of IU-Bloomington and received her Masters in Curriculum and Instruction at Purdue University. She and I led an educational exchange program between McCutcheon students and students in Pskov, Russia, in 2004.

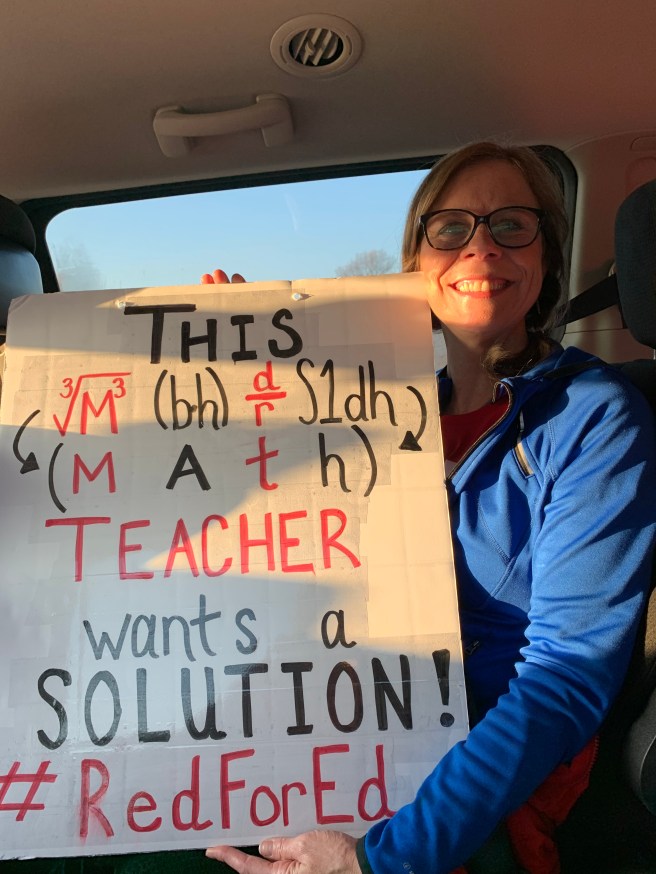

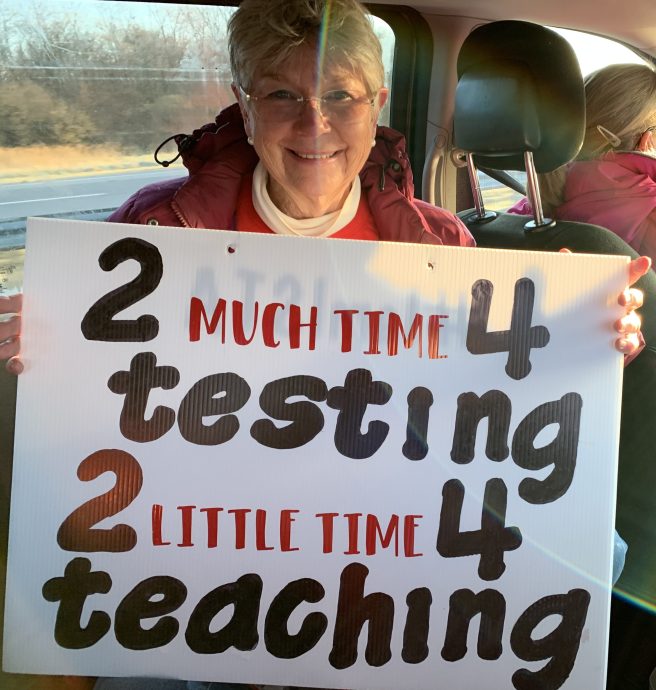

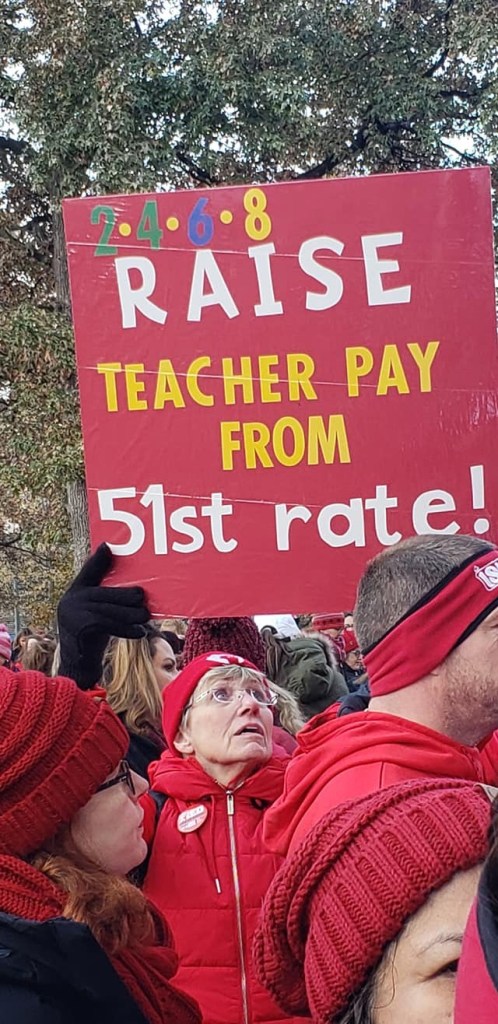

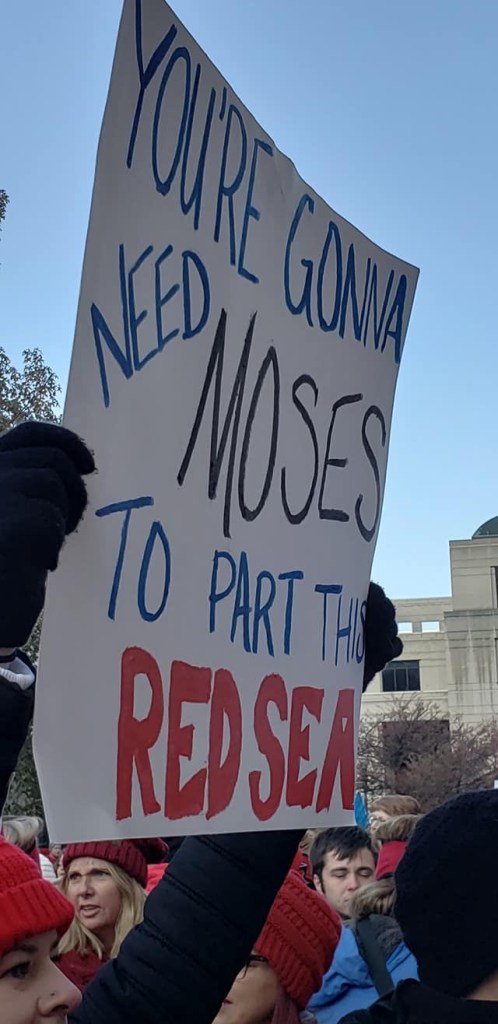

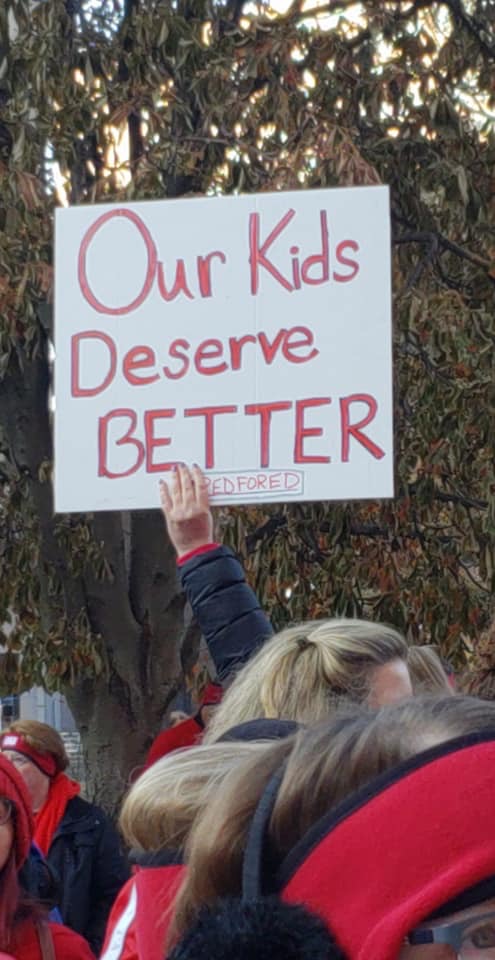

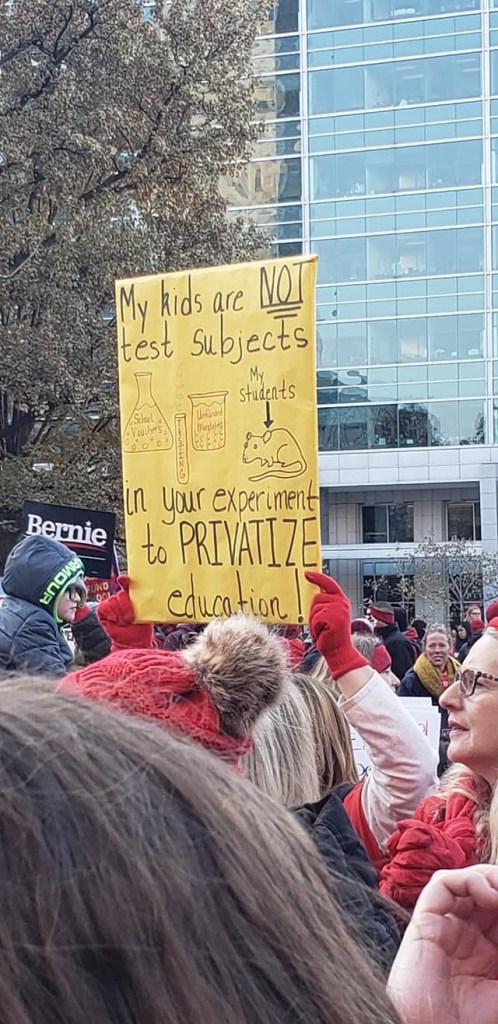

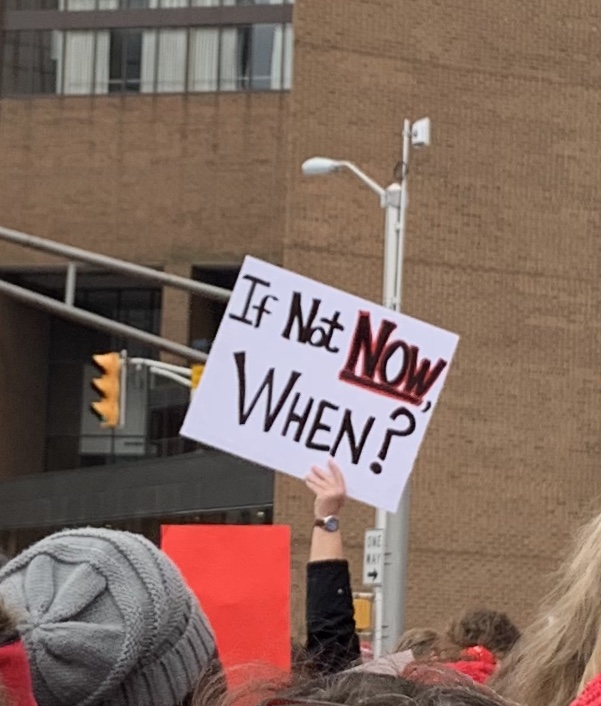

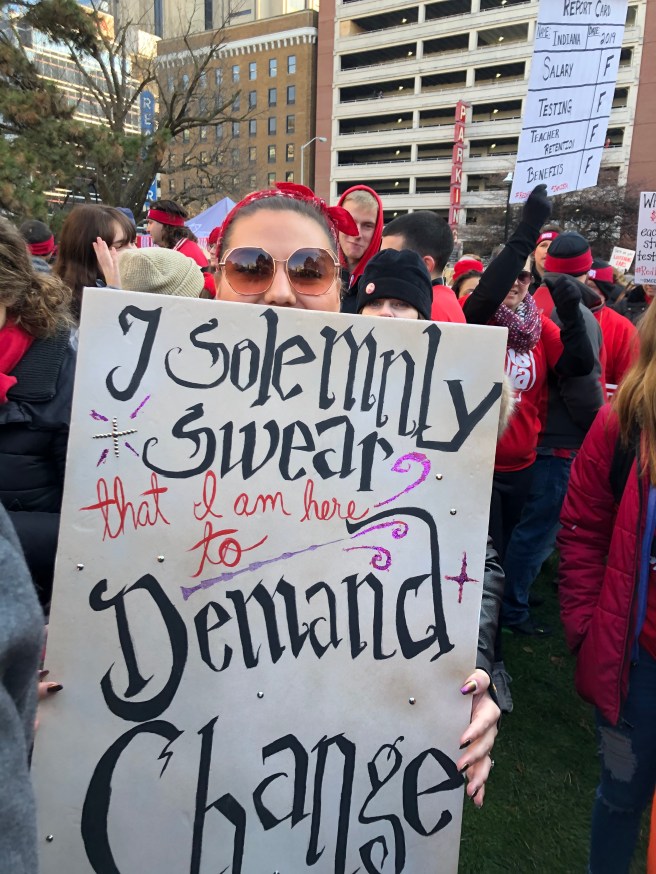

#Red4Ed

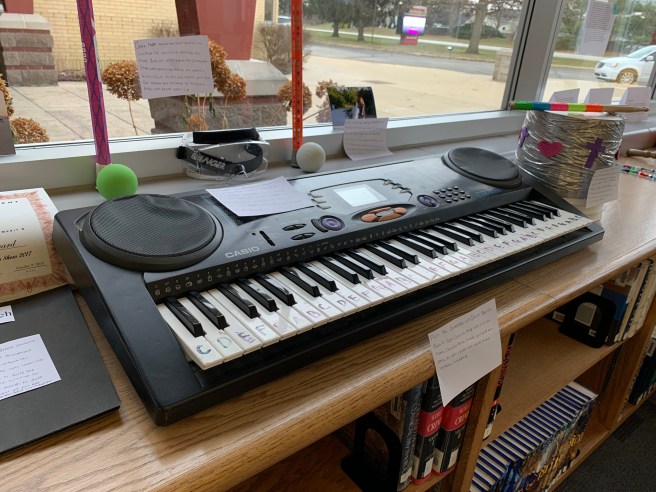

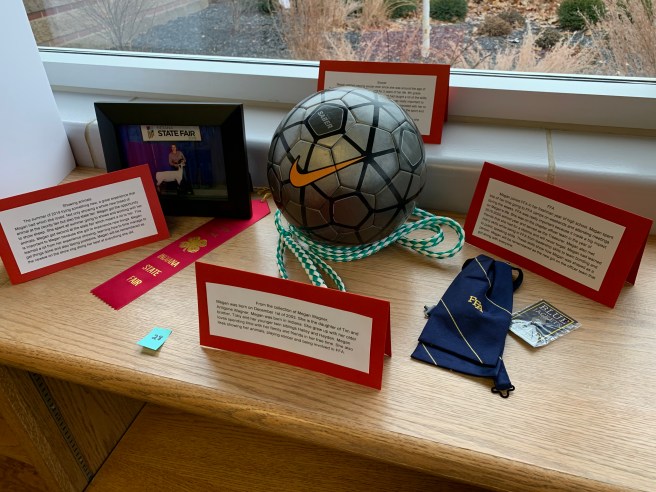

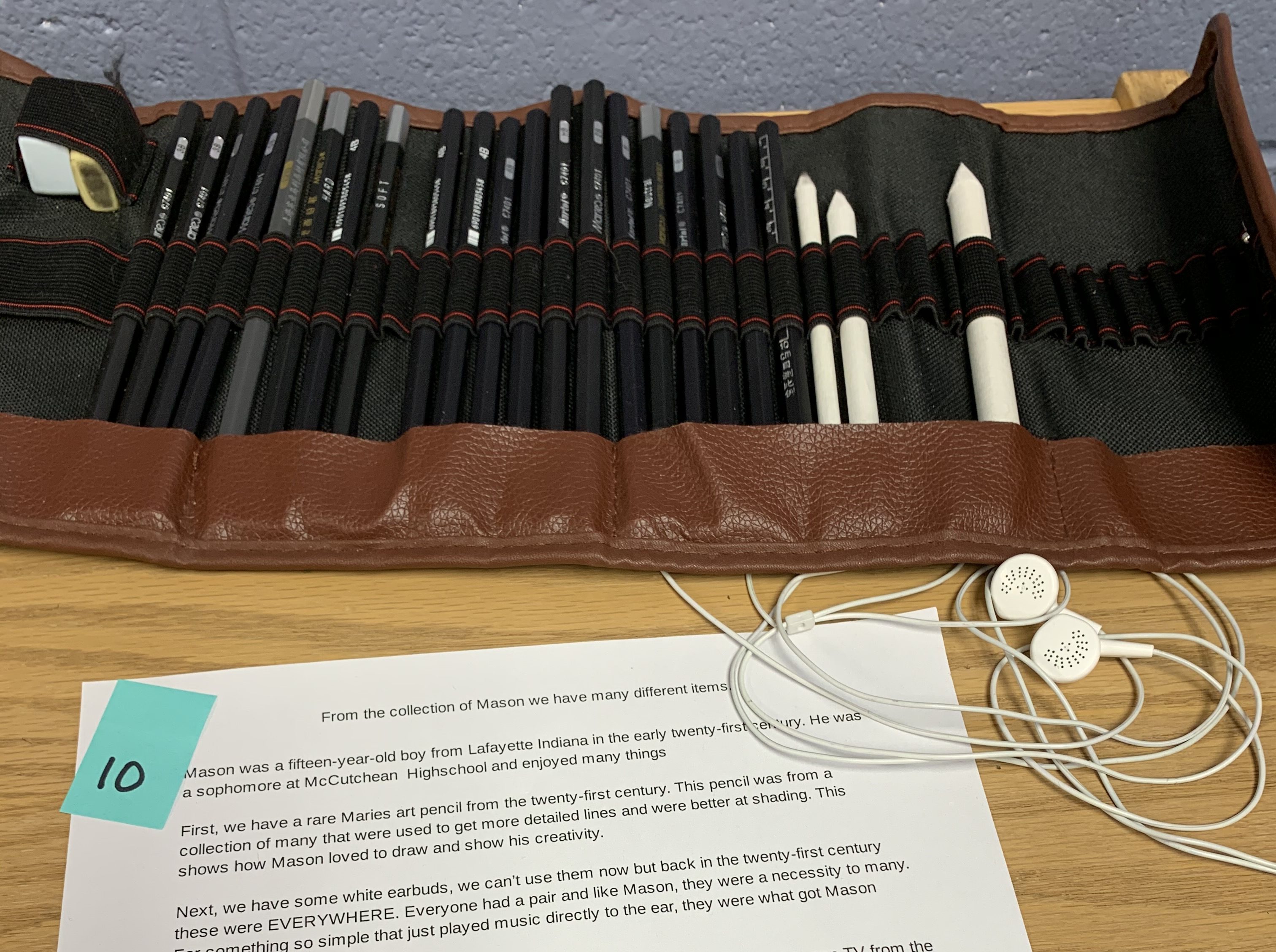

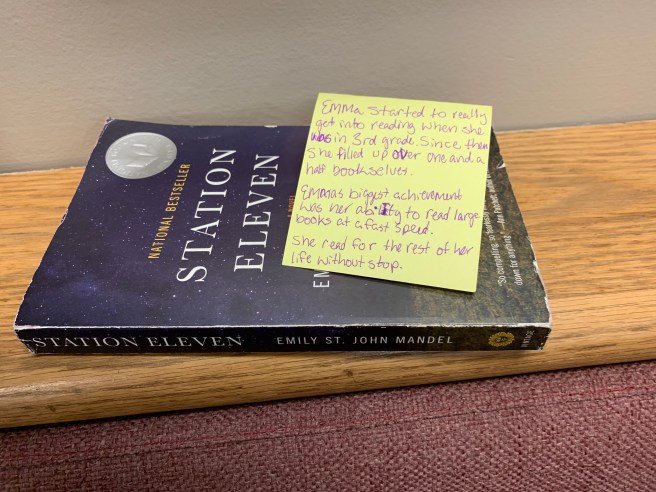

Yes, there were earbuds and screens, but not many. In fact, what I noticed in addition to the wide variety of artifacts was the overwhelming lack of electronics. Admittedly, Ms. Gessel forbade phones, but earbuds and other electronic paraphernalia did not dominate the displays. Instead, there were the indicators of family, friendship and faith. Of interest in the arts, organized sports, and individual artistic pursuits. In children, in 4-H, in books, in cooking. Ms. Gessel’s students, like most teenagers if critics would just look beneath the surface, are not the zombie-like, plugged-in and tuned-out youth so often caricatured. These are kids I want to know better, unique and interesting individuals who are going to be in charge of a world I want to live in.

Yes, there were earbuds and screens, but not many. In fact, what I noticed in addition to the wide variety of artifacts was the overwhelming lack of electronics. Admittedly, Ms. Gessel forbade phones, but earbuds and other electronic paraphernalia did not dominate the displays. Instead, there were the indicators of family, friendship and faith. Of interest in the arts, organized sports, and individual artistic pursuits. In children, in 4-H, in books, in cooking. Ms. Gessel’s students, like most teenagers if critics would just look beneath the surface, are not the zombie-like, plugged-in and tuned-out youth so often caricatured. These are kids I want to know better, unique and interesting individuals who are going to be in charge of a world I want to live in.

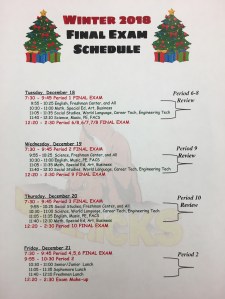

Almost the end of the semester. For high school students, the run-up to the holidays is likely to be stressful, thanks to those dreaded final exams. Guest blogger Mike Etzkorn, a math teacher who leads McCutcheon High School’s

Almost the end of the semester. For high school students, the run-up to the holidays is likely to be stressful, thanks to those dreaded final exams. Guest blogger Mike Etzkorn, a math teacher who leads McCutcheon High School’s